eBPF Agents Explained for Non-Developers

Rich Agent Poor Agent

eBPF is cool, powerful, niche, and very technical. This makes it the perfect smokescreen for some marketing extravaganza. I also take part of the responsibility for blowing smoke, but no more.

When I looked at ~40 eBPF-based products to understand the market, I haven’t looked at how well they implement eBPF. Partly because it was out of scope, but also because it’d be a long and difficult piece of work that I didn’t have the knowledge to carry out.

So now I looked into how to differentiate between a good eBPF agent and a bad one. A deep one and a superficial one.

A rich one, and a poor one.

Taking runtime security as an example, we can speculate how they would interpret a simple command to determine whether it’s malicious or not.

Rich vs Poor - Remote Code Execution Detection

Consider a remote code execution attack where an attacker exploits a web application to run the whoami command.

Poor Agent:

Detection rule includes

whoamias a suspicious behaviorAgent detects

execve(”whoami”)via syscall hookSees the syscall came from the web server process

Generates an alert

Rich Agent:

Detection rule includes

whoamias a suspicious behaviorAgent detects

execve(”whoami”)via syscall hookSees the syscall came from the web server process

Captures full stack trace showing the execution path:

HTTP request handler

URL parameter parsing function

Command injection point in vulnerable code

Shell invocation

whoamiexecution

Extracts the HTTP request that triggered the exploit (URI, headers, payload)

Correlates with the container, pod, and service identity

Identifies this as an anomalous execution path never seen in baseline behavior

Generates high-confidence alert with exact exploitation chain

Real-World Examples of Rich Agents

Here are some examples of rich runtime security agents that I know or that I found supporting documentation:

Oligo - identifies exploitation by tracing the command back to its true origin within the application’s execution flow.

Canopus - SuperNetflow can analyze encrypted traffic to distinguish between different application types

ARMO - Auto-creation of network policies and seccomp profiles based on observed runtime behavior

Upwind - uses eBPF to reconstruct API calls from socket-level traffic, even encrypted or undocumented ones.

Spyderbat - assembles eBPF data into a living temporal map based on causal relationships

Tetragon - ties network activity to a specific binary and identity that launched that connection.

Do you also do cool eBPF gymnastics? This is a living document so get in touch with me and I’ll add a short blurb above.

What an eBPF Agent consists of

Depending how you combine the below components and architect it with user-space processing, you can get complex logic that is not available in the user-space alone.

If you’re not an eBPF developer, you most likely have nothing to do with this information. But, it is useful understand what magic you can get out of eBPF.

Hook - eBPF hook is like a webhook, but for kernel events. It may be a backward way of thinking, but it helped me. eBPF programs are event-driven and are run when the kernel or an application’s hook points are triggered. Pre-defined hooks include system calls, function entry/exit, kernel tracepoints, network events, and several others.

Kprobes - If a predefined hook does not exist for a particular need, it is possible to create a kernel probe (kprobe) to attach eBPF programs to the ~40,000 other kernel functions that implement the actual logic.

Maps - store and retrieve data to be accessed by eBPF programs and applications in user space. Includes hash tables, arrays, and others.

Helper Calls - supporting functions such as generate random numbers, get current time and date, eBPF map access, get process, or manipulate network packets and forwarding logic.

Tail calls - mechanisms for chaining eBPF programs.

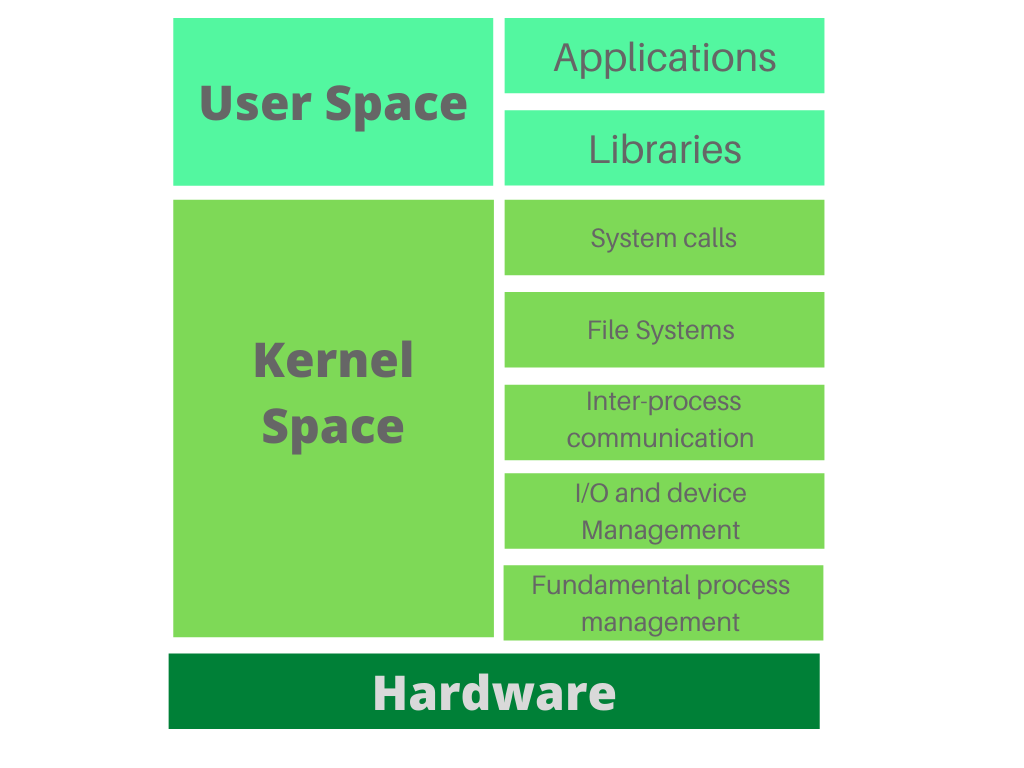

The Kernel-User Space Division of Labor

Understanding where processing happens is crucial to eBPF architecture:

Ref - https://uniandes-se4ma.gitlab.io/books/chapter6/monolithic-vs-microkernel.html

What Happens in Kernel Space (eBPF Programs):

Event capture and initial filtering

Fast-path decisions (allow/block based on simple rules)

Basic data extraction (syscall arguments, network packet headers)

Aggregation and counting (tracking frequency of events)

Writing filtered data to eBPF maps

Network packet manipulation (XDP for DDoS mitigation, load balancing)

Immediate enforcement actions (dropping packets, returning errors to syscalls)

What Happens in User Space

Correlation across multiple event types

Enrichment with metadata and external data sources

Behavioral analysis and machine learning

Communication with control planes

Policy management and rule updates

Generating detailed alerts with full context

Poor Agent

Poor agents typically attach to common system call hooks such as process execution, file access, network connections, and process creation. It does not differentiate between what processes take place or what connections are made.

Using such an agent to alert on suspicious syscalls such as attempting to open restricted files, won’t be able to see that:

The file open is followed by a network exfiltration over an existing socket

The process calling those syscalls is actually a child of an unusual binary

The same container instance recently made other suspicious operation

All this to say that without some detection and correlation logic, eBPF does nothing but extract some harder-to-get data.

Rich Agent

Rich agents interweave kernel hooks, maintain state, and correlate events in near real time to build the attack story. They correlate low-level kernel events with high-level application logic, user-space execution context, and runtime environment metadata.

French Braid-Level Hooking Strategy

Rather than just monitoring system calls, rich agents attach to multiple hook types simultaneously, including

Kernel-Level Hooks, such as system calls, LSM hooks, Kernel tracepoints, and memory management hooks like segmentation fault and memory operations.

User-Space Instrumentation, including function entry/exit points via uprobes, dynamic language runtime hooks, and library call interception.

Network-Specific Hooks, such as XDP for ultra-low-level packet processing, traffic control hooks for network shaping, and socket-level monitoring for L4/L7 traffic analysis.

Map Usage

Maps can act as state machines and store full execution paths from kernel through user space. It can be used to reconstruct the call chain that led to a security event. Other storage data include pod and container identifiers, image and namespace information, parent process lineage.

Data Enrichment and Filtering Logic

The enrichment pipeline generally starts in the kernel-space, then moves all relevant, correlated, and filtered data up to the user-space.

Kernel-space collection takes place when an event occurs the eBPF program runs in kernel space, where the agent can firstly filter based on simple rules such as "only capture network traffic on ports 80 and 443”. Events that don’t match criteria are dropped without ever leaving the kernel. Following that, the agent can extract arguments such as file paths, network addresses, syscall arguments.

User-Space sensor continuously reads from eBPF maps to retrieve captured events. The sensor maintains state across multiple events so it can, for example, correlate a network connection with the process that created it, track the parent-child relationship of processes over time, or link file access patterns to specific application workflows. The sensor can also pull metadata such as querying the Kubernetes APIs to associate processes with pods, containers, and deployments.

Response

eBPF across both the kernel and user spaces can respond to alerts. For example, if the sensor detects a compromised container, it updates a map with that container’s ID, and the eBPF programs start blocking all syscalls from that container.

Further Reading

If you want to learn how I learned when producing this article without any LLM prompting, feel free to read the following: